Vol. XXIII, Issue 1 (Winter 2016): Nigeria and South Africa

BOARD:

Gloria Emeagwali

Chief Editor

emeagwali@ccsu.edu

Walton Brown-Foster

Copy Editor

brownw@ccsu.edu

Haines Brown

Adviser

brownh@hartford-hwp.com

ISSN 1526-7822

REGIONAL EDITORS:

Olayemi Akinwumi

(Nigeria)

Ayele Bekerie

(Ethiopia)

Paulus Gerdes

(Mozambique)

Alfred Zack-Williams

(Sierra Leone)

Gumbo Mishack

TECHNICAL ADVISOR:

Jennifer Nicoletti

Academic Technology, CCSU

caputojen@ccsu.edu

For more information on AfricaUpdate

Contact:

Prof. Gloria Emeagwali

CCSU History Dept.

1615 Stanley Street

New Britain, CT 06050

Tel: 860-832-2815

emeagwali@ccsu.edu

Table of Contents

- Editorial: Professor Gloria Emeagwali

-

Kano Government, Nigeria and the Brain Drain - Muhammad Kabir Yusuf, Ph.D.

-

Brief Notes on South African Beadwork - Gloria Emeagwali and Mulungisi Shabalala

This issue of Africa Update explores various dimensions of African politics and culture in the context of Nigeria and South Africa. Dr. Muhammad Kabir Yusuf questions the real intentions and motives of Nigeria�s Kano State Government in sending students abroad to various countries, at a high cost to the state and its people. The brief article on beads reflects on the significance of South African beads in selected aspects of South African culture. In the course of discussion references are made to beads in ancient South Africa.

Professor Gloria Emeagwali

Chief Editor

AfricaUpdate

Kano Government, Nigeria and the Brain Drain

Muhammad Kabir Yusuf, Ph.D.

Nasarawa State University, Keffi, Nigeria

Introduction

Migration has been the major demographic feature of the 20th century (White, 2012) with Africa contributing more than its share of the migrants around the world. Sub-Saharan Africa has been at the disadvantaged side of the migration discourse owing to the internal contradictions of the region. In the typical narratives of the migration discourse, there seems to be a basic assumption. This assumption gives the impression that in the third world countries, scholars, civil rights organizations, governments, and concerned economic bodies often frown at the migration of the skilled-workers from the under-developed to the developed countries to the detriment of the smaller economies and to the advantage of the larger economies. Adepoju for example, would put it this way:

�A major challenge facing sub-Saharan Africa is how to attract back skilled emigrants, for national development � an aim which should be encouraged and supported by development partners and rich countries.� (Adepoju, 2007, P. 35)

Feeding on this perspective, some scholars crafted the derogatory term �brain - drain� to describe the phenomenon of skilled workers migration. To a very large extent, the phenomenon is associated with the economic retardation and instability of the African countries presumed to have lost a considerable size of their skilled -workers to the more vibrant and larger economies. It is associated with a huge economic lost for the countries of origin and a huge economic gain for the countries of destination of the workers. This particular line of narrative shaped many scholarly discourses that sought to explain the socio-economic impact of migration from especially, Sub-Saharan African.

However, this background

which sounds like a general rule has its exception. In the last three

years, the attitudes of Kano State Government towards migration are

inconsistent with the gospel that these scholars are preaching.

Exploring Kano state government�s �leftist� attitude towards skilled

workers migration is what gives this paper its relevance in the

discourse.

The

paper argues that Kano state government in Nigeria makes conscious

efforts to sponsor hundreds of individuals to migrate through

undergraduate and post-graduate scholarship schemes. This, the paper

argues, is a new trend in the brain-drain process and should make us

revise our understanding of the disadvantages of the brain-drain for the

countries of origin of the immigrants.

Research Methodology

Owing to the nature of the topic in question, this paper applies a qualitative research method. By using this research method, the paper intends to study the Kano State Foreign Scholarship program as a case study of a state - sponsored skilled workers migration.

Research Hypothesis

Kano State government is making conscious efforts to execute state-sponsored migration of skilled-workers.

The socio-economic impact of skilled-workers may form part of this paper but only as part of literature review. What the paper intends to cover is the fact that a conscious effort to execute state-sponsored skilled worker migration is a reality in at least some African countries. The motives behind this reality will be explored through the theoretical frame work.

Theoretical frame work: Colonial Mentality

Colonial mentality is an inevitable legacy of colonialism which most African countries experienced at some point in their historical development. Colonial mentality refers to an end product rather than the process. It is the situation in which the colonized has internalized the colonizer�s claims of superiority and subsequently, assumes the personality of the inferior specie at different levels. This is evident in the attitudes of the colonized in rejecting anything local and embracing anything foreign uncritically and unconditionally. Okazaki, 2006) explained the three layers of colonial mentality and the way they work in alienating an individual and society.

1. Covert Manifestation of CM

This is when the imposed inferiority is internalized by the colonized who begins actually to feel inferior and act inferior.

2. Overt

Manifestation of CM

3. Colonial

Debt

Conceptual Framework: The

Colonial Debt

Both at the community and

government levels, the city reached the third layer of colonial

mentality i.e. colonial debt having internalized the imposed inferiority

complex and passed through covert and overt manifestations of colonial

mentality. This alien reality, this paper argues, affected the thinking

process of the city as a collective being. This explains the reversal

order of the current thinking process of Kano community. Whereas the

city attracts immigrants as an African commerce center, today, the city

exports its skilled-workers at a very high cost in perpetuating service

to the colonial master.

Literature review

�rich in resources, it is the poorest of all regions. Civil wars and political destabilisation have severely eroded the developmental progress of the post-independence decades. In the present trend of globalisation and economic restructuring, SSA is the most disadvantaged. Rather than competing with the rest of the world, it must grapple immediately with more basic matters: poverty, conflicts and the HIV/AIDS pandemic � all of which impact severely on migration dynamics� (Adepoju, 2007, p.10).

As a result, the human

capital of the region is seriously under-tapped at various levels.

Unemployment of under-skilled persons and under-employment of the

skilled human capital and sometimes total unemployment became a

prominent feature in the region. This reality propelled in immeasurable

way the migration of skilled-workers to the richer countries.

Throughout the recorded history, Kano has always been a major commerce center in the Sub-Saharan Africa. To a very large extent, East African caravans of traders as well as immigrants from those areas played an important role in commercializing the city right from around 15th down to 19th centuries (Gwangwazo, 2007). In those days, Kano market and Businesses had been variously described as an impressive one. In the words of Henry Barth, the British-sponsored explorer as in (Barau, 2007: 22), �so well supplied with every necessary luxury in request among people� there is no market in Africa so well regulated�.

In the modern times, the official Federal Government�s census of 2006 put the population of the state at 9,383,682. Kano continued to claim its glory among the African cities, not only demographically, but also economically (Ado-Kurawa, 2008 b). It is one of the few Nigerian states with up to three universities, many vibrant markets and a huge film industry all of which provide enormous job opportunities for the populace. As of 2012, the film industry alone had more than 2000 registered companies.

Discussion

Recently, in Kano State of

Nigeria, the case has taken a new dimension. Migration from Kano has

become, this paper argues, fully sponsored by the government in the name

of undergraduate and Post-graduate Scholarship programs. This though

might not be the official stand of Kano State government, but the

language of the government is loud enough to communicate just that.

Starting from 2011, Kano

State Government has been executing a well-planned program to sponsor

about two thousand postgraduate students spending billions in Naira for

the success of the program.

The Beneficiaries Amount N Amount $

|

Batch A of 501

Postgraduate students |

N3,540,000,000.00 |

$ 21,474,064 |

|

Batch B 502 Postgraduate

Students |

N3,140,000,000.00 |

$ 19,047,616 |

|

300 Undergraduate

MBBS/Pharmacy |

N768, 767,370.00. |

$ 4,663,435 |

|

100 Pilot Trainees |

N1,200,000,000.00 |

$ 7,279,344 |

|

25 Marine Engineers |

N195,600,000.00 |

$ 1,186,533 |

|

10 Train the trainers

experts |

N50, 000,000.00. |

$ 303,306 |

|

197 ICT B.Sc. |

N200, 000,000.00. |

$ 1,213,224 |

|

50 Nurses for B.Sc.

Course |

N250, 000,000.00. |

$ 1,516,530 |

|

Total Number of the

Beneficiaries: 1687 |

Total N 9,344,367,370 |

$ 56,684,053 |

Looking at the way the

program is planned and executed as well as the utterances of the key

officials in the government, it is crystal clear that the government is

not just aware but also determined to execute a state-sponsored

migration under the pretext of a scholarship program.

�we have brought up this program in the hope that the underprivileged citizens will benefit from it. The program is so unique in that the beneficiaries are not required to come back and work for the government. Unlike similar programs in the past, the beneficiaries of this scholarship program are encouraged to find jobs wherever they can and we will be proud of our sons working abroad�1 (Kwankwaso, 2013)

Strategically enough, the English version of the speech, the content of which would normally be considered the official stand of the government does not contain such statement encouraging the scholarship beneficiaries to compete in the labour market abroad. This would leave an observer to assume that the statement in the local language was not more than �the euphoria of impromptu speech� meant to win the emotions of the beneficiaries and their relatives in the state. This perspective may sound logically correct given the reality that in Africa generally, the common man celebrates the fact that he has a relative who lives or works abroad. It is therefore, a valid argument to assume that the governor made this terrific statement playing on the emotion of the citizens to score a political goal.

After a year of this statement, it became clear that the agenda is much bigger than just scoring a political goal and identifying with the common citizens who celebrate living and working abroad. In a press release enumerating the successes of Kano State government, the Kano State Directorate of Press stated the following:

It is pertinent at this point to inform you that some of those postgraduate students have already secured employment with reputable organizations abroad and some have been upgraded for their PhD (Dantiye, 2014).

This is quite remarkable.

It is remarkable in the sense that the government is proud of the fact

that the huge fund invested in the scholarship as seen above is not

coming back home. This may appear a contradiction unless we get to

believe that this is the plan in the first place. It is more remarkable

considering the fact that 85 of the 502 candidates that made it to the

second batch list of the postgraduate scholarship were already working

with the government at the North West University. Subsequently, 16 other

persons were nominated to work with the government. As a civil servant

in the Nigerian government, it is generally an offence to refuse coming

back home after training or to take a job within or after the training

period. The Nigerian Civil Servant Act (2008) is clear about the fact

that an offender in this respect would be made to refund fully, the

funds allocated to them in the course of the training. To clear any

doubts, the governor of Kano State, Kwankwaso in an event organized for

the last batch of the beneficiaries of the �scholarship�, made a

statement that left no iota of doubt that the motive of the scholarship

is for the skilled-workers to join the brain-drain. In that respect, he

said the following:

�This scholarship program differs from the previous programs (by the previous governments), in the sense that the beneficiaries are not under obligation to come back and work for the government after graduation. In fact, the beneficiaries are encouraged to remain where they study and compete in the labour market for the available jobs. It is a fact that the government cannot provide job opportunities for all the beneficiaries. And we will be proud to have our children working all over the world�2 (Kwankwaso, 2014).

Conclusion

1. The policy makers are

completely clueless about the adverse economic implication of the

skill-workers migration in large population

2. The policy makers assume

that by helping skilled-workers migrate, they will be better off as

individuals and their individual economic gain will translate into a

huge economic gain for their home country as a result of their financial

assistance to their relatives back home. However, it will be ironic for

African policy makers to adopt the remittance argument. The remittance

argument is a line of thought advanced by apologists of Western

contribution to �Africa�s

economic misery� (Konhort, 2007).

3. African policy makers realized that the skilled population constitutes the enlightened force capable of checkmating their corrupt practices for which reason they decided to get rid of them by encouraging them to migrate and even went the extra mile to pay them to migrate.

Whatever the reason, there remains one all- important issue; the strange silence of Kano taxpayers, whose fortune is being used to facilitate the migration of the skilled-workers from the state. The only explanation for this phenomenon is the structural colonial mentality which makes the colonized pay the colonial debt in the form of continual servitude to the colonizer -psychologically and practically.

1 This impromptu speech was

given by the Governor in Hausa language and the translation to English

is done by this author.

2 This statement is rendered by

the author from the original language of the speech, Hausa, of

northern Nigeria.

Brief Notes on South African Beadwork

Gloria Emegwali and

Mulungisi Shabalala*

South Africans have developed mastery of beadwork, an activity that goes

back to antiquity. At Blombos, a site in the Northern Cape region,

perforated shells aimed at forming necklaces, show up as early as

100,000 BC (Henshilwood et al. 2001) and although the jewelry identified

from this very early period may not be classified as conventional

beadwork, the underlying concept and objective of the artifacts converge

with some aspects of later and contemporary South African beadwork.

Thousands of gold beads were also found at one of South Africa�s earliest Kingdoms, Mapungubwe, a kingdom that was located in the vicinity of the Limpopo and Shashe Rivers, parts of which are located in South Africa�s Limpopo Province. The beads, found in this region, and dated to around the eleventh century CE, were made of ostrich, snail and tortoise, wood, clay, ceramics, cowries, ivory, bone, iron, copper and gold- a range of organic, ceramic and metallic materials. It may be argued that contemporary bead culture in the South African case has roots in these earlier periods of South African history.

Beads on Children

Beadwork continues to be an

important part of South African Culture especially for black South

Africans. In the Zulu region, some of the earliest kinds of beads to

emerge were called Incwabasi, named after the local Syringa tree that

provided a major source of natural beads through its seeds.

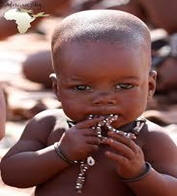

Figure 1 - Baby Wearing beads

The Syringa Beads are only worn by children aged between one week and 15 years. Its alleged purpose is to protect the child from malevolent spirits and to help a child grow healthily. These beads are round, small and grey in color. The bead maker makes use of fish wire to construct the necklace. A child wears the string of beads as a necklace or as a belt under the clothes directly on the body. The making of such beads is a source of employment in urban areas.

South African traditional healers use beads as a mark of identity to indicate their status and occupation. They do not choose the beads and beadwork on their own but allegedly would have been inspired by ancestral forces, in dreams. The traditional healer or sangoma dreams of the color of the beads to be worn through these ancestral, inspirational and psychic interventions. The color of the beads worn by the traditional healer has special meaning and significance and also reflects the source of the inspiration. For example, senior male ancestors are associated with red (indiki); while blue and black (Umndawu) indicate intervention by female ancestors, in general. White beads tend to be generic, indicating a wide range of ancestral spirits including those of children. We should note that the terms indiki and umndawu also have underlying significance in Zulu culture. For example refusal to take over from a previous sangoma could lead to a particular affliction associated with indiki.

Figure 2 - Beads worn by Sangomas

Beads and Courtship

Within the range of traditional healers in South African culture were

apprentices and initiates called Ithwasa, and trainers and teachers

within the ranks, called gobela. They are also associated with

particular colors and designs. Regional variations emerged over time.

Zulu speaking females between the ages of 15 years and 17 years wore

beads called Isigege which looked like beaded skirts and were made to

cover the legs. Isigege consisted of white beads and indicated purity.

In other age groups such as 18 to 20 years (Ijongosi) and 20 to 25 years

(Intombi), special types of beads were worn. The kind of beads worn

indicated whether there was readiness to engage in a relationship.

If you were ready to have a boyfriend you wore different kind of beads

called Ucu. If the female agreed to the advances and proposals of an

interested suitor, she removed the beaded necklace and gave it to him to

indicate acceptance of the proposal.

Red has a different meaning when worn by people who are not traditional

healers. Yellow symbolized wealth; white luck and orange attraction.

Green may indicate marriage

Marriage

In Zulu Culture, when a female exchanged

beads in the form of a white necklace worn around her neck, she

indicated approval of the advances made by a suitor. This marked the

first step in the relationship. The second step, involved the female

guide or escort, the Iqhikiza. The Iqhikiza was herself a virgin, who

educated girls about how to behave around males and informed the family

about the conduct of her prot�g�. She also visited the family of the

future bridegroom and handed over white beads and cloth to indicate her

approval. A date was then chosen and representatives from the male

partner visited the prospective bride.

Figure 3 - White beaded necklace

The male must keep wearing the white beads to show that he is now

engaged. This was followed by elaborate exchange of gifts on both sides.

We should note that beads played a central role in the unfolding

relationship from inception to the eventual marriage. After marriage

beads of green became important symbols.

Figure 4 - Marriage ceremony

Notes

-

Christopher Henshilwood et al. (2001). An early bone tool industry

industry from the Middle

Stone Age at Blombos, South Africa. Journal of Human Evolution.

41.631-678.

-

Alexander Duffey et al.(2008) The Art and Heritage Collections of

the University of Pretoria.

Pretoria:

University of Pretoria Press. pp. 26 -50.

About the Author*

is a local historian in

Soweto, South Africa

http://www.siyayenzalento.co.za